2000, zero-zero, party over: Colette Shade looks back to the turn of the millennium

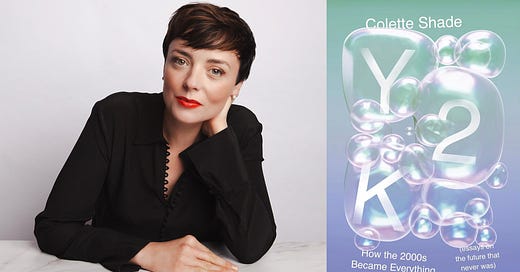

The author of the essay collection "Y2K: How the 2000s Became Everything" discusses the not-so-distant past and the disappointing present.

Journalist Colette Shade says her new book, Y2K: How the 2000s Became Everything (Essays on the Future That Never Was), came out of a sense of disillusionment with the present day. “I’m very concerned about the political situation and about climate change and about the economic situation, all of which I consider to be connected,” she tells Depth Perception. “Since the [first] election of Trump, and then especially around 2018, when there were really bad wildfires in California and some really bad hurricanes, I’ve just been feeling hopeless.”

As a result, Shade, who was born in 1988 and has written for The New Republic, The Baffler, Gawker, and more, says she found herself “retreating into nostalgia, following all of these Instagram accounts that had scans of, like, Seventeen magazine from 1999 or 2003.” Those were the years when she was coming into political consciousness, when the new millennium promised “unlimited growth and prosperity for all.”

Y2K looks back on that hopeful time with verve and wit, through essays like “Only Shooting Stars Break the Mold” (that’s a Smash Mouth lyric) and “Larry Summers Caused My Eating Disorder.” Writing the book, Shade says, “helped me make sense of my own life story, but also helped me understand the historical narrative better.”

Shade, who is based in Baltimore, recently spoke with Depth Perception via Zoom. The following interview has been condensed and edited for length and clarity. —Mark Yarm

Why did you become a journalist?

When I was a kid, I wanted to write fiction. And I was writing fiction through my twenties — not particularly successfully, although when I was in high school, I did win a YoungArts award, which is a national arts award. Timothée Chalamet won one for acting [in a different year], so that’s pretty cool.

Everyone was always telling me, “You have to write a novel.” This is like the 2000s, the Y2K era and the years after it, when novels had much more kind of cultural power. I tried to do that for a long time, and it just didn’t work out. And I started writing these essays, and it turned out I was pretty good at writing creative nonfiction essays. I’ve been a freelancer since 2014.

What story of yours are you proudest of?

I wrote a really viral piece for Gawker in 2015. It was like a lot of these longform journalism pieces where it’s nominally about one thing, but it’s really about 10 other things. It was nominally about this horse race in Baltimore horse country that’s a very popular social event for the Southern gentry–type people there. This horse race happened to be while there was unrest in Baltimore around the death of [Freddie Gray], who was killed by police, and so I went and I talked to people about that.

I got some interesting quotes. It almost presaged MAGA, because it was in 2015 and I imagine a good number of the people there overlap with the people who were at the Trump rally stories that all the long form journalists did. I really liked that I was able to weave together all of these different things. What I really like to do is that old school magazine-style journalism, where you’re weaving in personal narrative, you’re weaving in historical stuff, you’re weaving in cultural observation.

What story of yours do you most regret?

Around 2017, I had horrible writer’s block. I was just feeling really frustrated, and someone from The Week asked me to write for them, and I was like, Crap, what do I pitch them? And so I pitched them this story about how nude shoes were associated with MAGA or something. It was a very specious argument, and I was really grasping for straws. Even a week after it was published, I was like, Well, that was very stupid, and I don’t even agree with the thing that I just said, and I certainly don’t agree with it now.

September 11, 2001: “The hinge on which so much changed.”

“What happened on 9/11 and how it changed our world is the most important story of the modern age,” says host Garrett Graff in the first episode of Long Shadow: 9/11’s Lingering Questions. “It’s the hinge on which so much changed — the dividing line between the 20th Century and the 21st.”

That day, many watched the tragedy unfold live on television, but most still don’t understand what happened. Nearly 25 years later, a third of Americans are too young to even remember the attacks. While thorough, large-scale efforts like the 9/11 Commission tried to make sense of that chaotic day, many questions remain.

The first season of Long Lead’s Edward R. Murrow Award-winning podcast Long Shadow attempts to answer those questions and explore other enduring mysteries of that day. Hailed as “rigorous, authoritative, and an electrifying listen” by The Financial Times, the eight-episode limited series quickly became Apple’s number one history podcast. Listen now, wherever you get your podcasts.

What’s the best journalistic career advice you ever received?

“Stop writing fiction.” Who told me that? My agent. Why? Because it’s just really hard to sell. And then it turned out that I actually like writing nonfiction better.

What’s the worst journalistic career advice you ever received?

“You should totally go to journalism school,” which I never did. Journalism school, in my opinion, is mostly stupid — especially these days, since there just aren’t the jobs anymore. They don’t pay you — typically you pay them — whereas something like an MFA actually makes a good amount of sense if you do the type of MFA where they pay you. You’re essentially getting two years to be paid to write whatever the hell you want. And then you’re also making these connections — and I guess that really is what journalism school is about. You’re essentially buying a social network. But, for journalism, that doesn’t make sense anymore, because there aren’t the jobs to be had.

Which of your articles or essays should be made into a movie?

Some of the ones in the Y2K book could certainly. Maybe “My uncle got rich in the dot com bubble.” It’s about how my uncle went from countercultural ’60s guy to working in Silicon Valley in the ’70s, ’80s, which is a pretty common trajectory. He made a bunch of money in the dot com bubble, and changed his life and my life. It shaped my perspective on what I thought the 21st century would be like, because I was a kid, I was 11, and I was like, Oh, I guess in the 21st century, everyone's just gonna get rich overnight. And that’s just obviously not true.

But I don’t think my uncle would like that one very much, because I don’t think he wants people to see a movie about him. Maybe the whole Y2K book should be made into a movie, and it’s a political coming-of-age story about a millennial from the late ’90s through 2008.

What was the most indulgent media event you ever experienced?

This was December 2016 — the Outline’s Christmas party that they did with Cadillac. I don’t know if it was a nightclub or just like a weird industrial venue in Chelsea. There were blowup aliens, like giant inflatable stuff. I want to say it was a space theme, but I could be wrong. And I was there with the members of Chapo Trap House, my friend Gabriela Barkho, Ziwe, and a bunch of other people. It was like the last hurrah of 2010s digital media money. You had a really strange combination of people who were in digital media, or emerging from it, and people from GM corporate. But it was fun! I miss it. Bring it back. Cadillac, please fund more journalism!

What makes you think journalism is doomed?

Everything? There just aren’t enough full time jobs, and it’s just not realistic for everybody to have a Substack, because not everyone can be Matt Yglesias and make a million dollars a year. Also, it doesn’t make sense for people from a personal financial level, because with a newspaper, you’d pay like $1,000 a year, but you would get, like, a bajillion writers. And now you have to pay that, and you get much less bang for your buck.

What makes you hopeful for the future of journalism?

The one big, positive change that I’ve seen so far is the unionization movement. For any kind of change, unions are our best bet, because they’re the only thing that can really put a wrench in things, and really hit people in the pocketbook in a way that posting and having a protest just can’t do. It’s been really, really good to see this massive wave of unionized newsrooms. It also means that the messages that are getting put out by the media are much more pro-union than they were, for instance, in the Y2K era, where the general attitude was, Oh, unions are old-fashioned, and we don’t need them anymore. So that gives me hope.

Further reading from Colette Shade

Y2K: How the 2000s Became Everything (Dey Street Books, 2025)

“The Future That Never Came” (Slate, Dec. 31, 2024)

“My uncle got rich in the dot com bubble” (User Mag, Jan. 7, 2025)

“Elon Musk Has Always Been Like This. So Has Silicon Valley.” (The New Republic, Nov. 14, 2024)

“Alex Kazemi on Columbine, Content Warnings, and New Millennium Boyz” (Interview, Sept. 12, 2023)

“‘Baltimore Is a Shithole’: Undisturbed Peace at the Maryland Hunt Cup” (Gawker, April 28, 2015)