Through family road trips, Sarah Kendzior discovered America’s fate isn’t sealed just yet

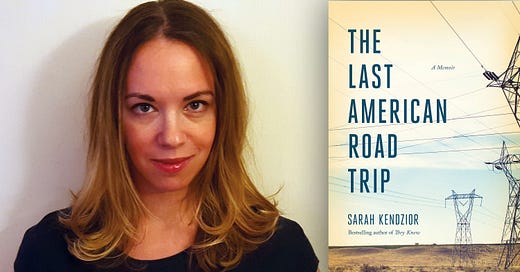

In her new memoir, the journalist and academic used the United States’ open roads to show her children what’s worth preserving.

Summer is here and with it, the familiar rhythms of road trip season across the U.S. But in a time of mounting political instability, climate anxiety, and economic precarity, journalist and author Sarah Kendzior uses road trips not as a means of escape, but as political revelation for herself and her family.

In her new book, The Last American Road Trip, Kendzior transforms the winding paths of middle America into a prescient exploration of a nation in flux. From abandoned mines turned tourist attractions in nowheresville to Mark Twain’s unassuming hometown beneath glowing skies, Kendzior illuminates all of it through her lens as a political analyst and scholar. Aside from being an author, she has served as a columnist for The Globe and Mail and Al Jazeera English, and has written for outlets like The Guardian and Foreign Policy to cover authoritarianism and digital politics.

Known for her coverage of the Trump era circa 2015 in books like Hiding in Plain Sight and They Knew, Kendzior has long written about the corrosion of democratic institutions and the people caught in its wake. But The Last American Road Trip marks a new turn: Part memoir, part political reckoning, it meditates on parenthood, memory, and bearing witness to a country confronting its own fragility.

Depth Perception spoke with Kendzior about her latest work and why, even now, she refuses to believe America’s fate is sealed. —Kelly Kimball

You’ve reported on American political decline for years, but The Last American Road Trip brings a different, personal lens to this unraveling. What did writing from within your own family’s experience reveal that political analysis alone could not?

This book kind of began after I had written a book called Hiding in Plain Sight in 2020, which is more of investigative journalism looking at 40 years of political corruption along with the rise of Donald Trump. The epilogue of the book was about what I was doing with my family as a mother of two young children, and how I was trying to take them to as many national parks as I could before something bad happened.

From that point onward, I wanted to write a book that was just about the experience of taking road trips with my family across a rapidly changing America — changing for political reasons, changing for ecological reasons, changing because of COVID. I wanted to encapsulate not just the decline, but what we loved about it, what we looked forward to seeing, what we wanted to protect and preserve. I really wanted my children to see these places firsthand before something worse happened to them.

In your new book, you describe your mission is to show your children America “before it’s too late.” What does “too late” mean to you, and do you think we’ve already crossed that line?

I don't think there's exactly such a thing as "too late." In part, that's informed from living in Missouri, where we've been living in the aftermath of these policies and this destruction for a very long time. There are places I write about that are just quintessentially Missouri, like you have an abandoned mine and you turn it into an "underground kayaking adventure" when it floods. There's another place called the Nuclear Waste Adventure Trail, which is a hiking trail just over a mound of nuclear waste. We are so used to taking destruction and abandonment and violence and turning it into entertainment.

You have to be very imaginative to survive living here, and you begin to appreciate all of the overlooked and subtle beauty around you. You find that beauty in the wreckage. It's with that mindset that I would drive with my family in every direction. We weren't just looking for the splendor and wonder of a place like Glacier National Park. There's a lot of overlooked sites along the way.

It's hard for me to answer the "too late" question, because on one hand, I feel like we crossed it long ago, and a lot of people have just been catching up. If you ask somebody who's Native American, they're going to say that they crossed that line hundreds of years ago. If you ask people who are descendants of enslaved Black Americans, they're going to have a different response. And the answer for everyone is you just keep going anyway. You keep going and you try to find meaning in your life, for your family, for your country, [and] for your community.

“You have to be very imaginative to survive living here, and you begin to appreciate all of the overlooked and subtle beauty around you. You find that beauty in the wreckage. It's with that mindset that I would drive with my family in every direction.” —Sarah Kendzior

Your book takes readers through iconic venues like Route 66, national parks, and historical landmarks. Can you share a moment or place that crystallized the themes you’re exploring?

One of them was when I took my kids to Florida. And I don't mean Florida, the state — I mean Florida, Missouri, population zero. It's the hometown of Mark Twain. Before COVID, I had promised my children we were going to go on an actual trip to Florida, the state, which became impossible. So we drove out to Florida, Missouri. They didn't know where we were going. I kept telling them, "Get excited. We're going to Florida."

We went to Mark Twain's hometown, which has this sign saying that he "soothed an aching world." They put up that sign in 1913, and I kept thinking, "My God, they had no idea what was around the bend." They didn't know World War I was coming. They didn't know the Spanish flu was coming. So I felt this deep sense of kinship with that.

But then we found a pond near that site, and we waited for it to get dark. And this is in such an isolated area that you can see all of the stars. My kids were very disappointed that we were not in the actual Florida, and I said, "Just wait. It'll get good." And then we were able to see the Milky Way.

A hundred years ago, most people around the world had seen the Milky Way. Now you really have to drive somewhere to be able to see it. I didn't see it myself until I was 40, and when I saw it… I cried because I just couldn't believe how beautiful it was. And I also couldn't believe that I'd been missing it my whole life.

That was a special moment, because we were obviously traumatized and frightened by the [COVID-19] pandemic, but I was still determined to try to show my children something good without compromising our safety, and I was able to do that with them.

How do you reconcile these extremes — seeing the Milky Way with what you’ve described as this sense of brokenness from an emergent autocracy?

I've been warning about Trump since 2015 that he was going to rule as an authoritarian kleptocrat. What I'm worried about much more now is technology. I'm worried about AI. I'm worried about surveillance, and I'm worried that people are getting a very false view of the world through their phones — not just through propaganda, but through fake images, bot people… because they feel like they don't have a friend to talk to. And I think that we have a class of oligarchs and plutocrats who see human beings as disposable, and they see the qualities that make us human — our imagination, our compassion, our curiosity — as irrelevant.

But another reason to travel to places and see them face-to-face is the serendipity, the surprise of the journey. When you see people face-to-face, when you see how folks are living, I think it does expand your sense of empathy. Local media has been gutted for such a long time that I don't think there's an accurate representation of how people are feeling.

A history podcast that’s vitally relevant to America’s current politics

The recent launch of Long Shadow: Breaking the Internet — the fourth season of the Long Lead’s Garrett Graff-helmed podcast — is retracing 30 years of web history, leading listeners to America’s current, fractured, moment in time. But readers of Sarah Kendzior’s work may want to rewind and binge Long Shadow: Rise of the American Far Right, the podcast’s Edward R. Murrow Award-winning second season that connects the dots between the Ruby Ridge raid, the Waco siege at the Branch Davidian compound, the Oklahoma City bombing, the January 6 insurrection, and other explosive events in recent U.S. history. How did America get the far right so wrong? What will it take now to get it right? Listen and subscribe wherever you get your podcasts.

As someone from the Midwest who has traveled extensively through the region, what do you think is underreported about how a second Trump administration is affecting people on a personal, day-to-day level?

I think it's an incredibly unpopular administration. And the thing is, the Democrats are also an incredibly unpopular party. Most people… feel betrayed. They feel let down and abandoned.

I think the Great Recession [in 2008-2009] is something that most regions never recovered from. We were told that it was a recovery, but that just made the pain worse. People thought, "Well, if the economy is booming, then why can't I find a job? Why am I working three-gig jobs?" Then they gradually realized it wasn't their fault. But unfortunately, you have people like Trump taking advantage of that pain, which is genuine pain.

I like this excerpt from your book: "I search for truth and justice and wind up on the American way, a path of pain and violence that permeates from past to present, yet even in the worst of times, I refuse to believe our nation's fate is preordained." What do you think it will take for a non-preordained fate in the U.S.?

I think it takes brutal honesty and transparency about state crimes and about the complicity of U.S. officials, regardless of what party they are in. The Republicans have gone to great lengths to censor American history and to ban the teaching of accurate American history in schools — things like slavery or Native American genocide — in part because they don't want people to see the parallels that are emerging in contemporary life. But there's also incredible denial among the Democrats that this has been a party of enablers, particularly for Trump.

When you tell the whole truth about something, no matter how ugly it is, that is the way to get there… There's a sense of, "Oh, we can't say anything bad about our party, because it gives the other side power." It doesn't. If you're already in the position where you're self-censoring, then you have already lost your power. The reason you tell the truth is to protect people. It's to protect what we have left.

Further reading from Sarah Kendzior

“Trump’s America, where even park employees have become enemies of the state” (The Guardian, January 28, 2017)

“Trumpmenbashi: What Central Asia’s spectacular states can tell us about authoritarianism in America.” (The Diplomat, March 22, 2016)

“The Healthcare Bill Exposes Trump's Chilling Authoritarian Agenda” (Marie Claire, May 9, 2017)

“It’s Already Happened Here: Trump is a familiar figure, a manifestation of deep-seated will-to-white-male power” (The Baffler, February 9, 2017)

“Welcome to Donald Trump’s America” (Foreign Policy, August 3, 2016)