Revising Sports Illustrated

The first draft of the magazine's history omitted adventure writer Virginia Kraft. Seven decades later, outdoor journalist Emily Sohn sets out to discover why.

Pioneer Woman

In the Mad Men era of the 1950s, the golden age of Manhattan magazine publishing, Virginia Kraft toiled away anonymously at Field & Stream. The classic hunting and fishing title was a place where a woman’s byline would scarcely appear, usually next to first-person opinion pieces upholding rigid gender stereotypes like “I Married a Fisherman.” Her work was never published under her name. Readers knew Kraft as “Seth Briggs,” the “Outdoor Questions” columnist.

Then, in 1954, Kraft left the publication to join a new weekly magazine Time Inc. was launching called Sports Illustrated. Dedicated to the stereotypical, red-blooded American man who had a love of beautiful women and the minutiae of sport, SI became a household name. And while she spent a 26-year career there writing adventure features, Kraft did not.

Long Lead’s latest production, THE CATCH, written by outdoor and environmental journalist Emily Sohn, profiles one of most important, unheralded sports journalists of her time. A pioneering writer who chiseled early cracks into publishing’s male-dominated world, Virginia Kraft shared the same pages as legendary journalists George Plimpton, Frank Deford, and Roy Blount, Jr. So why hasn’t anyone heard of her?

Kraft was SI’s preeminent hunting and outdoors writer, producing more than 100 bylines across her career. She wrote deeply reported and immersive features, just like her male colleagues, while quietly racking up an unrivaled collection of achievements. A competitive skier who raced sailboats and hot-air balloons, Kraft hunted with kings and drank with Hemingway. She was the first woman to compete in a major dogsled event in Alaska, and likely the only mother of four to traverse six continents to take down all Big Five trophy animals.

Kraft created her seat at the journalistic table by owning her beat. She got her start when a Field & Stream editor realized if he hired her, he could pay her a third of what he paid her male counterparts. Kraft shrewdly understood that despite the pay gap, she’d still make three times more than she would reporting on hemlines for a fashion magazine. “She kind of bullshitted her way into the job,” a friend of Kraft’s confides to Sohn in THE CATCH. Kraft had never hunted in her life when she attended that job interview.

A competitive skier who raced sailboats and hot-air balloons, Kraft hunted with kings and drank with Hemingway.

These types of contradictions abound in Virginia Kraft’s life and career. She traveled the globe for her stories, yet made sure her kids had home-sewn Halloween costumes. She loved animals, but hunted them with expert skill. She was a pioneer for women in journalism, yet no one has recognized her contributions as a trailblazer.

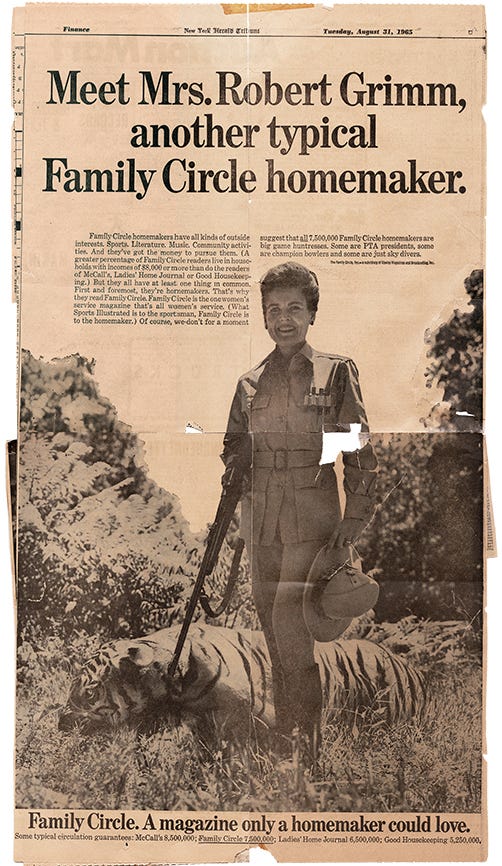

Why was Kraft lost to history? Was it misogyny or something more? For instance, SI editors promoted her work by revealing that she wore Chanel No. 5 during her weeks-long hunting expeditions. In 1970, she appeared as an editor on the masthead of SI, a rarity for a woman of that era. Time Inc. was a notorious boys’ club in mid-20th century America (as well as a former employer of mine and Long Lead founding editor John Patrick Pullen). Other press reports covering her work frequently mentioned her appearance. The juxtaposition of her dual role as homemaker and hunter was even used in a newspaper ad to help sell subscriptions to Family Circle magazine.

In exploring Kraft’s biography and body of work, Sohn uncovers what she calls “a complicated story of a woman who did not fit into simple boxes, and whose career challenged my expectations of what it means to be a pioneer.” She does this while re-reporting one of Kraft’s features, experiencing first-hand the challenges women journalists faced nearly 70 years ago — and still face today.

“In a post-MeToo world it's hard to explain, even to myself, how I could have not consciously recognized that my gender might have been one of the reasons it took me 20 years to achieve one of my career goals, even as I saw younger male writers breaking in,” Sohn writes. “And I'm not the only female sports journalist who feels this way.”

Why was Kraft lost to history? Was it misogyny or something more?

As the old saying goes, journalism is the first draft of history. One of the first things a researcher examines when studying a specific time period are the contemporaneous media accounts of the era being studied. These artifacts can give a sense of what life was like “back then.”

First drafts, however, get revised, and Sohn’s deeply reported, contemplative piece not only grapples with Kraft’s legacy, but also with what it means to be a woman in journalism today. Accompanied by rich archival images, lush video and photography by Kathleen Flynn, and an evocative, classic magazine design with a modern spin by Gladeye, it’s the kind of journalism that only Long Lead can produce. I encourage you to spend some time with this production and reconsider Virginia Kraft’s life and work.

So long for now,

Heather Muse

Audience Development Director, Long Lead

PS: Long Lead will publish several more productions in the coming weeks. As a subscriber to this updates list, you’ll be hearing from us more frequently. If you want to read about the world of longform journalism regularly, subscribe to our DEPTH PERCEPTION newsletter. The next edition will feature an interview with Emily Sohn about her experience writing THE CATCH.

If you’re reading this because you subscribe to DEPTH PERCEPTION and received this piece via crosspost, you can subscribe to the Long Lead updates newsletter below.